By JANE GROSS

My mother was a nurse, the old-fashioned kind without a college degree, first in the class of 1935 at the Lenox Hill Hospital School of Nursing in New York City. Her graduation was announced in The New York Times, and her name was listed in the commencement program — Estelle S. Murov, in gold letters on ivory vellum —as the valedictory speaker, to be followed by the Florence Nightingale Pledge, presentation of prizes and diplomas, benediction, recessional and a reception and dance at the Hotel Astor.

In the dozen years that followed (until my birth), she wore a blue flannel cape and a starched white cap while presiding over the preemie nursery at Lenox Hill, long before the days of neonatal intensive care units. The glory years for nurses, my mother always told me, were during World War II, when most of the doctors were away and real responsibility replaced being a handmaiden.

white cap while presiding over the preemie nursery at Lenox Hill, long before the days of neonatal intensive care units. The glory years for nurses, my mother always told me, were during World War II, when most of the doctors were away and real responsibility replaced being a handmaiden.

With this as my background, I am hardly a disinterested reviewer of a new anthology of essays by 21 nurses. It is beautifully wrought, but more significantly a reminder that these “semi-invisible” people, as Lee Gutkind calls them in this new book, are now the “indispensable and anchoring element of our health care system.”

Today, there are 2.7 million registered nurses working in the United States, compared with 690,000 physicians and surgeons. That number is expected to grow to 3.5 million in the next half dozen years, Mr. Gutkind writes in his introduction, as members of the baby boom generation require hospitalization and home or hospice care.

After he had selected 21 essays from more than 200 submissions, Mr. Gutkind had personal experiences that drove home the very thing the nurses wrote about over and over. He spent several months at others’ hospital bedsides — his mother, 93; his son, 21; his uncle, 86; and a friend, 72 — and rarely saw a physician.

Though it is the doctors who are considered “deities,” he writes, it was the “irreplaceable” nurses who were a source of comfort and security during his family’s multiple trials. And yet by his own admission he took them for granted — “I cannot not tell you what any of the nurses looked like, what their names were, where they came from” — which is exactly the state of affairs my mother described 65 years ago.

She would have loved this book, and no passage more than the one in which Tilda Shalof, a nurse for 30 years and also a best-selling author, describes “the ongoing tension between the university-educated nurses like me and the old guard, the hospital-trained, diploma-prepared nurses.”

The latter, she argues, are preferable. “Maybe those veterans didn’t know much about research or nursing theories, but they sure know how to care for patients,” she writes. “They knew how to get the job done. I wanted to be like them — a nurse who could start IVs on anyone.”

Many of the nurses who have contributed to this anthology are also part-time writers or bloggers. I would have welcomed some information from Mr. Gutkind, the editor of a literary magazine and writer in residence at Arizona State University, about whether nurse/writers are common and if so why. Perhaps many of them write because they rarely talk about their work, as they point out in these essays, and are encouraged in training and by the medical hierarchy to be tentative, even submissive, in their communication with doctors.

Several of the essayists describe their duties as tedious but the implications as profound. Eddie Lueken, a nurse of 30 years who also has a master of fine arts in creative writing, described her student years, earning tuition money busing tables at a steakhouse where she had to wear a cowboy hat and went home smelling like A.1. sauce. She yearned for the adrenaline rush of paddling people back to life; instead, she wound up mastering bedmaking, denture care for the terminally ill and measuring the diameter of bed sores.

Her first opportunity to give an injection involved morphine for a woman with metastatic breast cancer, her respiration already so low that the narcotic might kill her. For that reason, the night nurse had skipped the patient’s scheduled pain medication.

Her first opportunity to give an injection involved morphine for a woman with metastatic breast cancer, her respiration already so low that the narcotic might kill her. For that reason, the night nurse had skipped the patient’s scheduled pain medication.

Now Ms. Lueken’s supervisor was leaving the decision to her: “Crossing her arms, she looked me in the eye” before asking, “ ‘Should you give a dying woman with advanced bone cancer her pain medication, or withhold it because she may stop breathing?’ ”

“I’ll give it,” Ms. Lueken said, mostly because it was more exciting than “turning patients like they were logs.” Her reward: “Good job” written in a neat hand on her daily clinical evaluation, and the news from the charge nurse the next morning that her patient “went quietly” just a few hours after she had left for the day.

Never in her essay does Ms. Lueken say that what she had done was good nursing. But another nurse, Thomas Schwarz, also a published writer, effectively does it for her. He chose, at 63, to switch from nursing in emergency rooms to working the quiet night shift of a home hospice nurse.

“Everyone I’ve ever known, loved, kissed, sat next to on a bus, watched on TV or hated in the third grade is going to die,” Mr. Schwarz wrote. “Everyone. And I am the midwife to the next life for some.”

When you think of a nurse, what’s the first image that comes to mind? Chances are, you think of a woman — and for good reason. The vast majority of professional nurses in the U.S. are white women. In fact, only about six percent of nurses are male and, Considering males make up approximately half of the population and minorities are 30 percent, there’s a major disparity in the profession.

When you think of a nurse, what’s the first image that comes to mind? Chances are, you think of a woman — and for good reason. The vast majority of professional nurses in the U.S. are white women. In fact, only about six percent of nurses are male and, Considering males make up approximately half of the population and minorities are 30 percent, there’s a major disparity in the profession.

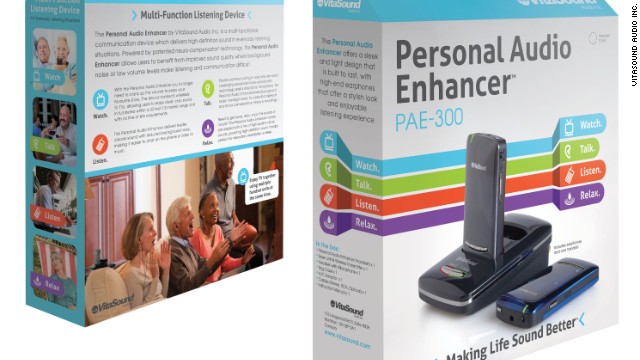

From "let there be sound" to "let there be light," the next Father's Day gadget is the

From "let there be sound" to "let there be light," the next Father's Day gadget is the

The

The  Source:

Source:  As a health care giver, you have a responsibility to ensure that they have adequate knowledge in order to provide competent

As a health care giver, you have a responsibility to ensure that they have adequate knowledge in order to provide competent