In today’s increasingly diverse healthcare landscape, language and culture are far more than communication tools, they’re fundamental components of high-quality, patient-centered care. When language barriers exist, so do significant risks: misdiagnoses, poor adherence to treatment, patient dissatisfaction, and even preventable harm. Bilingual and bicultural Nurses play a critical role in closing these gaps, ensuring every patient receives care that is not only clinically effective but also culturally sensitive and respectful.

The Impact of Language Barriers in Healthcare

Healthcare is complex, even for those fluent in medical terminology. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), understanding a diagnosis, medication instructions, or discharge plan can feel nearly impossible. According to research, LEP patients are more likely to experience longer hospital stays, higher readmission rates, and poorer outcomes compared to English-speaking patients.

Miscommunication can lead to:

-

Errors in medication dosing or timing

-

Missed follow-up appointments

-

Poor understanding of self-care instructions

-

Anxiety and mistrust in the healthcare system

These challenges make the presence of bilingual healthcare professionals, especially Nurses, who spend the most time with patients, indispensable.

Bilingual Nurses: Communication Beyond Words

Bilingual Nurses do more than translate words, they interpret meaning, tone, and context. This ability enhances every aspect of patient care, from assessment and education to emotional support.

Benefits of bilingual Nursing care include:

-

Accurate Assessments: Patients are more likely to describe their symptoms and concerns fully when speaking their native language.

-

Improved Health Literacy: Nurses can explain complex medical information in a way that’s clear and relatable.

-

Increased Compliance: When patients truly understand their care plans, they’re more likely to follow them.

-

Trust and Comfort: Being able to speak in one’s first language fosters connection and reduces anxiety.

Cultural Competence: The Power of Bicultural Nurses

Language is only part of the equation. Culture deeply influences health beliefs, decision-making, and perceptions of care. Bicultural Nurses, who share or deeply understand their patients’ cultural backgrounds, are uniquely positioned to bridge these differences.

They can anticipate potential barriers, such as:

-

Preferences for traditional remedies or holistic approaches

-

Cultural norms around gender, modesty, or family involvement

-

Differing views on pain expression, end-of-life care, or mental health

By integrating cultural understanding into care, bicultural Nurses promote respect, dignity, and individualized care, core components of Nursing practice.

Real-World Impact: Building Trust and Better Outcomes

The presence of bilingual and bicultural Nurses has tangible benefits for healthcare systems and patient outcomes. Studies show that patients cared for by culturally and linguistically concordant providers report higher satisfaction, better communication, and improved adherence to treatment. Hospitals and clinics with diverse Nursing staff also see fewer disparities in care and better community engagement.

Moreover, these Nurses often serve as cultural ambassadors within healthcare teams, educating colleagues on best practices and helping shape policies that promote inclusivity and equity.

Supporting and Expanding the Bilingual Nursing Workforce

As patient populations continue to diversify, the demand for bilingual and bicultural Nurses will only grow. Healthcare organizations can support this vital workforce by:

-

Offering language proficiency training and certification programs

-

Providing incentives for bilingual skills

-

Recruiting from diverse communities

-

Creating mentorship and leadership opportunities for bilingual Nurses

Language and culture are powerful determinants of health and Nurses who can navigate both provide more than care; they deliver connection, understanding, and healing. Bilingual and bicultural Nurses are essential to bridging healthcare gaps, ensuring every patient is seen, heard, and cared for with compassion and respect.

As the face of healthcare evolves, so must the people delivering it. By embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in Nursing, we move closer to a truly inclusive healthcare system, one that meets patients where they are and empowers them to achieve their best possible health.

In our growing diverse society, health care workers need to understand that applying only traditional westernized medical practices isn't appropriate for many patients and families. Health professionals must have an awareness of different cultural practices and spiritual beliefs in order to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

In our growing diverse society, health care workers need to understand that applying only traditional westernized medical practices isn't appropriate for many patients and families. Health professionals must have an awareness of different cultural practices and spiritual beliefs in order to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care.

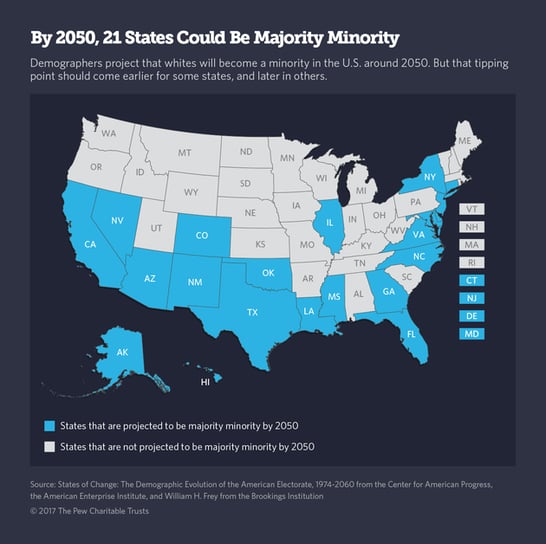

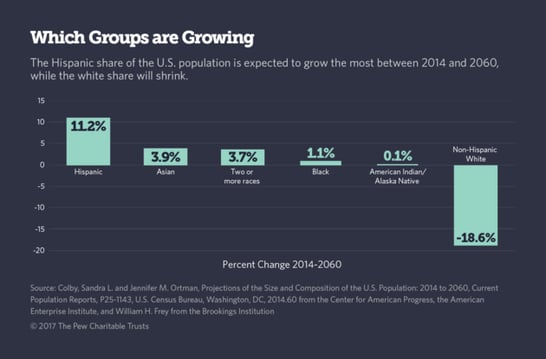

The U.S. population is growing increasingly diverse. By 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau projects less than 50% of the children in the U.S. will be non-Hispanic and Caucasian. With demographics shifting, health care professionals trained in cultural competence will meet the needs of community health more effectively. Nurse practitioners earning their

The U.S. population is growing increasingly diverse. By 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau projects less than 50% of the children in the U.S. will be non-Hispanic and Caucasian. With demographics shifting, health care professionals trained in cultural competence will meet the needs of community health more effectively. Nurse practitioners earning their

Frontier Nursing University conference discusses healthcare diversity

Frontier Nursing University conference discusses healthcare diversity

Depending upon your physical location of employment, whether it’s in the city, suburbs or rural area, you may encounter language barriers with your patients every day or maybe only once or twice a year. Whatever the frequency is for you, it’s important that the information you have to deliver is conveyed as clearly as possible. Some medical terms we use here in the US may not have clear translations in your patient’s native language.

Depending upon your physical location of employment, whether it’s in the city, suburbs or rural area, you may encounter language barriers with your patients every day or maybe only once or twice a year. Whatever the frequency is for you, it’s important that the information you have to deliver is conveyed as clearly as possible. Some medical terms we use here in the US may not have clear translations in your patient’s native language. Growing up, we were taught to be modest. As we became adults and more comfortable with who we are as a person, modesty may have become more important in our lives, or perhaps, less important. It depends on our personal circumstances and beliefs.

Growing up, we were taught to be modest. As we became adults and more comfortable with who we are as a person, modesty may have become more important in our lives, or perhaps, less important. It depends on our personal circumstances and beliefs. How can you properly care for a patient if you don’t understand their personal needs? Communication is key. Making a patient comfortable goes far beyond providing warm blankets. It is about the patient trusting you and knowing you have things in common that show them you understand how they feel and what they need.

How can you properly care for a patient if you don’t understand their personal needs? Communication is key. Making a patient comfortable goes far beyond providing warm blankets. It is about the patient trusting you and knowing you have things in common that show them you understand how they feel and what they need.

Cultural respect is vital to reduce health disparities and improve access to high-quality healthcare that is responsive to patients’ needs, according to the

Cultural respect is vital to reduce health disparities and improve access to high-quality healthcare that is responsive to patients’ needs, according to the