You take care of people in your job every day. However, if the tables are turned because you became ill and now it’s you being taken care of, the situation is bound to introduce you to a different perspective on how things feel.

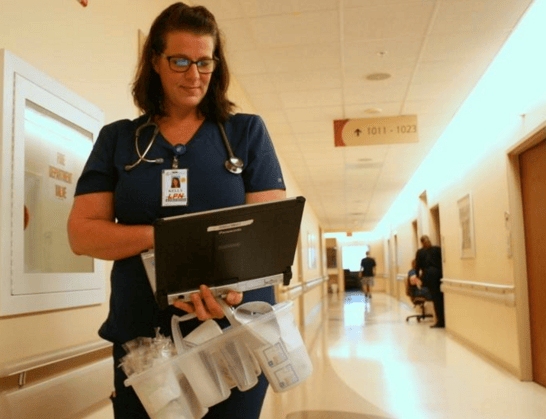

You take care of people in your job every day. However, if the tables are turned because you became ill and now it’s you being taken care of, the situation is bound to introduce you to a different perspective on how things feel. The squeak of tennis shoes moving quickly across the linoleum floors adds to the cacophony of alarms and beeps pulling nurses and doctors in every direction on the acute care floor of Florida Hospital Memorial Medical Center.

In the midst of the commotion, nurse Kelly Northrip sits quietly at the bedside of a patient, listening with the kind of intensity that doesn't come natural to most.

"I get told all the time I spend too much time with my patients, so to speak, and I say there is no such thing," said Northrip, a licensed practical nurse. "Each one is a learning experience."

Northrip knows firsthand the impact a few extra moments can have on a patient. If any of her patients doubt her, she might tell them about the golf ball-sized tumor that was discovered on her brain or the surgery she endured, answering doctors' questions while they probed her brain.

Usually, it's enough for Northrip simply to be there for her patients, hearing their concerns and reassuring them that everything will be all right. She's experienced that firsthand as well.

A DREAM THREATENED

After 18 years in the restaurant industry, Northrip embraced a career change to pursue her dream of becoming a registered nurse. After graduating and starting her career as a licensed practical nurse, Northrip's newly established career was almost sidelined forever when a tumor was discovered in her brain last summer.

Overnight, the career she had worked so hard for was in jeopardy, and so was her life.

Northrip's specialists presented her with three options: do nothing; do a biopsy and determine how to proceed; or, the riskiest option, an awake craniotomy.

"Doing nothing wasn't an option for me, for us," said Northrip, whose husband and two kids supported her decision to go with the most aggressive option.

In an awake craniotomy, the patient is awakened after surgeons open the skull. That way doctors can ask a series of questions while removing the tumor and ensure other areas of the brain aren't damaged.

Sounding just like an eager nursing student, Nothrip described the prospect as "scary and exciting at the same time."

"I was more nervous than she was," said her husband, Steven.

But the surgery is rare — and risky. Her doctors recommended that she seek out surgeons who were specialists in the procedure.

"He said you'd be better off going somewhere where they've done thousands. If it won't bankrupt you, go to Duke," she recounted. On a morning in August 2016, Northrip and her family loaded up into her brother's motor home to drive from Florida to North Carolina so that the drowsy Northrip could sleep during the trip, a symptom of the tumor. After three blown tires, and countless frazzled nerves, the motor home delivered them safely to Duke University Hospital where Northrip would undergo brain surgery the next morning.

Northrip remembers being wheeled into the operating room for the surgery, where a big TV on the wall showed images of her brain. After being put to sleep, Northrip awoke to a bright room full of people and the distinct sensation of pressure in her head.

"I could feel the doctor working in my head," she recalled. "I could feel him working in there and I actually spoke to him and he spoke back. I could feel discomfort, but not great pain."

As the surgical team began to remove Northrip's tumor, they asked a series of questions to ensure they didn't affect other areas of her brain.

"He had me move my feet, wiggle my toes, do a number of things. I just tried to relax, and they tried to keep me calm through the whole thing. I can remember almost everything. I can even remember their faces."

The surreal experience of being conscious during brain surgery left Northrip feeling "very much awake and alive."

The next thing Northrip recalls is waking in a recovery room, feeling like she was being hit in the head with a hammer — proof she had survived the surgery.

The pain subsided when Northrip received the news she had hoped for — the tumor was benign, and she wouldn't have to undergo chemotherapy.

"The only thing I would be required to do was an MRI every year," she said.

Other challenges still lay ahead.

THE RECOVERY

While insurance covered a large portion of the rare surgery, Northrip and her family still had numerous medical bills to pay on top of regular living expenses. Family, friends and coworkers rallied to the family's aid, hosting golf and dart tournaments and online fundraising campaigns.

"It makes you think, 'What did I do to deserve this?' I don't look in the mirror every day and say I'm a wonderful person. I don't think you ever feel deserving," Northrip said. "You're just trying to do your thing, trying to be a good, decent person and do things to the best of your ability."

The outpouring of support continued into Christmas when her family was adopted by the hospital staff, who bought presents for the kids. Northrip's co-workers also provided gift cards for the family.

The financial help allowed Northrip to focus on recovery and her goal of getting back to the job she loved. She pushed herself hard through physical therapy with the goal of coming back to work quickly but learned she couldn't force her body to recover faster than was possible.

The emotions of the recovery caught her off guard.

"I didn't think anything about the after, I just jumped in (to the surgery) with both feet and thought I would deal with it as it came," she said. "It was a very eye-opening, learning experience."

Physical therapist Donna McQuade worked with Northrip and knew the obstacles she would have to overcome to return to the job.

"When you do the job every day, you forget what it takes," McQuade said. "But having had such an extensive surgery, I don't think she was aware how much it affected her emotionally."

True to her persistent nature, Northrip tried to come back ahead of schedule, only to realize she wasn't ready and needed to continue her physical therapy.

"She's been doing it for so long she just didn't realize how much strength it took" to work a nursing shift, McQuade said.

Northrip persisted, and in January she returned to work.

"It's really miraculous, the amount of time from when she found out she was sick to when she was back to work," said McQuade.

While the experience challenged Northrip in more ways than she expected, being on the other side of the bed brought her a rare perspective that changed the way she views her job.

"Prior to this, I could only sympathize with my patients," Northrip said. "But after being hospitalized I can truly empathize and identify their anguish and stress."

To her coworkers, there was little doubt she would return and be a better nurse for her experience.

"We knew she would be back and rise to the challenge," said McQuade. "She's got a good support system here because she's a good support system to us."

Being back at work has also allowed Northrip to pursue her original goal, to become a registered nurse.

After years of applying to a full program, Northrip's application was recently accepted and she started school to become a registered nurse — while also returning to work.

"Ironically, I didn't expect it to be happening my second week back to work. I kind of bit off more than I could chew," Northrip said. "I don't take it lightly. I know it's a privilege for me to be working where I am. I want a better life for me and my family and help others to the fullest extent."