By Debra Wood

While among the most rewarding professions, nursing is not without its challenges. Nurses are exposed to numerous risks, sometimes with life-changing or life-ending consequences, such as nurses who died during the SARS outbreak or lost their lives falling asleep at the wheel after a long shift. Most adverse events are more mundane, but a back injury can end a career and a needlestick can pose serious health risks.

To keep you healthy and safe, NurseZone.com queried a panel of experts who share this list of 10 reminders and tips on how to minimize the chance of nursing job-related injury or illness:

1. Clean your hands

“Wash your hands to prevent illnesses’ spread,” said Arvella Battick, MSN, RN, PHN, an instructor at Everest College in Anaheim, Calif.

When it comes to illnesses, my number one rule is to wash your hands, agreed Jumi Harris, MHA, MT (ASCP), manager of ancillary services at Levindale Hebrew Geriatric Center and Hospital. It “sounds very basic, but this is the best way to avoid getting sick.”

2. Use the lift and transfer equipment

My number one way to avoid injuries on the job is to use lift devices instead of trying to lift a patient or resident manually, said Harris, adding, “Sometimes a nurse may think it’s too time consuming to get and use a lift or that the person is not too heavy. However it only takes one wrong move to injure yourself, so my advice is always use a lift device with the proper training and protocols.”

Renee Watson, RN, BSN, CPHQ, CIC, manager of infection prevention and epidemiology at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, added that nurses should use the appropriate equipment to lift anything heavy, such as soiled linen bags.

3. Watch for hazards and practice good body mechanics

Practice ergonomics and good body mechanics, suggested Watson.

Battick recommended nurses watch for hazards and keep the environment free of clutter. If there’s something on the floor, pick it up. Don’t just step over it.

Nurses should wear supportive shoes and watch for fall risks for themselves, not just their patients, advised Nick Angelis, CRNA, MSN, author of How to Succeed in Anesthesia School (And RN, PA, or Med School). Changing positions and muscle movements helps minimize pain and discomfort over time. Rotate tasks between hands, he added, and avoid hunching over to chart or care for a patient; elevate the patient’s bed, or, when documenting, find a place to sit or stand straight.

4. Speak up and step up

Whether dealing with a potentially violent patient or just needing a hand to move someone or something, ask a colleague for help.

“It’s safer to transfer with two people,” said Battick, but she acknowledged that help is not always available.

On the other hand, step up and offer your assistance to peers, as well.

5. Get vaccinated for the flu

People working in hospitals, clinics and other care settings are at greater risk of acquiring the flu and of transmitting the disease to patients and peers.

Influenza is a contagious disease that could spread by simply sneezing and coughing, explained Tanielle Sterling, MSN, NP, clinical program manager for employee health at The Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. “Combating the myth of getting the flu through vaccination is the biggest challenge in improving compliance rates. By getting the flu vaccine, you protect yourself and may avoid spreading influenza to your patients, colleagues and your family.”

6. Immunize against other pathogens

Immunize the body and keep good immune health, advised Watson at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, which requires nurses stay current with hepatitis B, tetanus and diphtheria, the measles, mumps and rubella series and influenza vaccinations.

“Hepatitis B infection is an occupational health hazard that is preventable by vaccination,” Sterling said. “All direct-care providers should be screened for hepatitis B surface antibody and offered the vaccine series. Education on the importance of completing the series and infection control practices helps to heighten awareness, change practice and attitudes towards vaccination.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends health care workers be vaccinated against the highly infectious hepatitis B, a bloodborne pathogen that can remain infectious on surfaces in the environment for at least a week. The vaccine produces a protective antibody response in more than 90 percent of people after the third dose.

Healthcare workers born in 1957 or later without serologic evidence of immunity or prior vaccination should receive the measles, mumps and rubella series, varicella, and tetanus and diphtheria vaccines.

7. Practice safe needle handling

Do not recap needles, and use needless connection systems, advised Watson.

Each year, hospital-based health care personnel experience 385,000 needlestick- and sharps-related injuries, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). This equates to an average of about 1,000 sharps injuries per day in U.S. hospitals.

Mary Foley, PhD, RN, chairperson of the Safe in Common campaign to prevent needlestick injuries, called it essential that nurses and other members of the health care industry work together to raise awareness of these types of injuries and find ways to prevent them in the future.

“Nurses need to be sure that the safety mechanism on needlesticks is automatic and will not interfere with normal operating procedures and processes,” Foley said. “Activation of the safety mechanism should also not create additional occupational hazards or cause additional discomfort or harm to the patient. Perhaps most importantly, the used safety devices should provide convenient disposal and mitigate any risk of reuse or re-exposure of the nonsterile sharp. Following these rules will help to ensure that nurses are safe from the threat of needlestick injuries so that they can remain healthy and active for their patients.”

8. Don personal protective equipment (PPE) as appropriate

Take no shortcuts when it comes to protection against bloodborne pathogens. Always select and wear the appropriate gloves, gowns, masks, eye protection and other items to prevent exposure to patients’ body fluids. Such equipment places a barrier between the hazard and the nurse.

Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta promotes using PPEs when clinicians know or suspect the patient has a communicable disease. Watson advised, “If it’s not your wet, put something between you and it,” and “protect your eyes, nose and mouth from coughing.”

9. Get plenty of sleep

Multiple studies, including “Fatigue, Performance and the Work Environment: A Survey of Registered Nurses,” published in the Journal of Advanced Nursing in 2011, from the University of Missouri in Columbia, have found that fatigue negatively influences nurse performance.

In the book, Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, Ann E. Rogers, PhD, RN, FAAN, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing in Philadelphia, warned that “in addition to jeopardizing patient safety, nurses who fail to obtain adequate amounts of sleep are also risking their own health and safety.” She pointed to the risk associated with drowsy driving, the increased chance of accidents of all sorts and that one’s immune system rarely works at peak performance when the body is tired.

10. Practice good self-care

Physical health requires overall wellness and staying strong, Watson said. Children’s in Atlanta promotes a holistic approach that includes daily exercise, good nutrition and fitness. It offers fitness classes and unit-based stretch breaks. Buddy coverage often is available for nurses who want to take a quick walk or class. Wellness includes obtaining psychosocial support when needed, particularly after dealing with emotionally taxing situations, such as participating in debriefings after traumatic incidents or seeking professional help through an employee assistance program.

When you’re sick, stay home and rest, Battick added.

Angelis recommended “exercising, packing nutrient dense foods for lunch; ingesting probiotics, either as supplements or in foods such as kefir or traditionally cultured vegetables; and staying well rested are all ways nurses can keep their immune systems in great shape against the barrage of germs that assault us daily.”

Source:

Nurse Zone

© 2013. AMN Healthcare, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

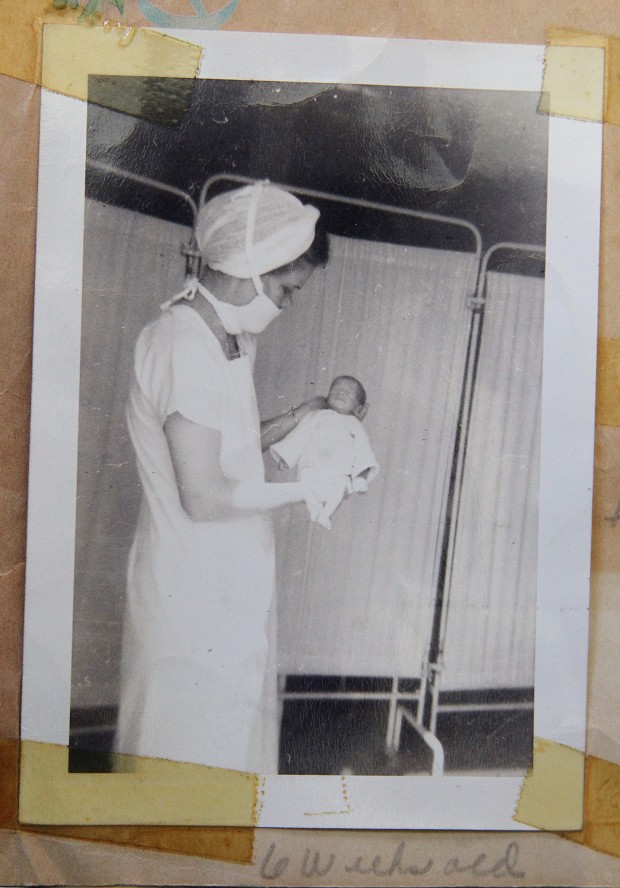

there — remembers feeding Bolles a teaspoon of breast milk from a medicine dropper every hour.

there — remembers feeding Bolles a teaspoon of breast milk from a medicine dropper every hour. Our brain is divided into left and right hemispheres. The left is the logical, linear and reasoning side while creative, intuitive and artistic operations reside in the right side. We all use both parts daily, but our culture strongly encourages the exercise of the left hemisphere.

Our brain is divided into left and right hemispheres. The left is the logical, linear and reasoning side while creative, intuitive and artistic operations reside in the right side. We all use both parts daily, but our culture strongly encourages the exercise of the left hemisphere.