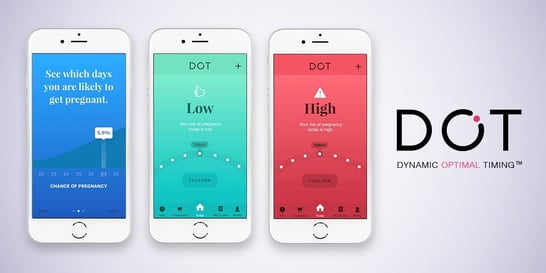

Do you worry about family planning with some of your patients? If so, this article about an “app” that helps to avoid unwanted pregnancies may be helpful. “Dot” is the only family planning app that relies solely on period start dates. Health experts believe an estimated 225 million women worldwide are not using effective family planning methods, but want to avoid pregnancy.

Do you worry about family planning with some of your patients? If so, this article about an “app” that helps to avoid unwanted pregnancies may be helpful. “Dot” is the only family planning app that relies solely on period start dates. Health experts believe an estimated 225 million women worldwide are not using effective family planning methods, but want to avoid pregnancy.

The Dot app will be studied over a year. If used correctly, researchers in an earlier study found the app is almost 100% effective at avoiding an unwanted pregnancy. Continue reading below for more details about the study and more information about the Dot app.

Researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center’s Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH) announced the launch of a year–long study to measure the efficacy of a new app, Dot™, for avoiding unintended pregnancy as compared to efficacy rates of other family planning methods. The Dot app, available on iPhone and Android devices, is owned by Cycle Technologies. Up to 1,200 Dot Android users will have the opportunity to participate in the study.

The study, funded by a grant from U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), will be the first known study to examine how women use a fertility app in real–time and to evaluate its effectiveness at avoiding unintended pregnancy. In a previous study, a research team found that Dot is theoretically 96 to 98 percent effective at avoiding unintended pregnancy if used correctly. As a woman continues to use it, the app increases its individual accuracy.

While there are thousands of menstrual cycle tracking apps on the market, recent research has demonstrated that the majority are not accurate enough to avoid unintended pregnancy or plan a pregnancy. One study evaluated 100 fertility awareness apps. Only six could correctly identify the fertile window. This finding highlights the importance for app–based family planning tools to rely on scientifically–backed methods and to be evaluated thoroughly for their accuracy.

“Our new study is unique because we’re testing the efficacy of Dot as a method to avoid unplanned pregnancy in a real–time situation,” says Rebecca Simmons, PhD, a senior research officer at IRH.

The study will evaluate Dot’s efficacy in avoiding unplanned pregnancies using a protocol that allows researchers to compare the results to known efficacy rates of other family planning options. It will also explore social factors, such as how Dot affects relationships. The researchers will recruit participants through Dot for Android, issue surveys in the app, and interview participants four times during the study. Participants will receive a gift card each time they enter period start date information and each time they complete a survey.

The IRH study could have global significance because multiple studies suggest that the main reason women stop using the birth control pill is side effects. If Dot can help women avoid pregnancy without the pill’s high abandonment rate, it’s a compelling alternative, says Simmons. The app would be especially useful in the developing world, where there is significant unmet family planning need. Global health experts estimate that 225 million women worldwide are not using effective family planning methods but want to avoid pregnancy.

“Dot users have a historical opportunity to advance the science of birth control and family planning,” said Leslie Heyer, president and founder of Cycle Technologies. “No fertility app has undergone such rigorous testing. Users who join our effort can help make free, effective fertility tools accessible to women throughout the world.”

Cycle Technologies developed the science and algorithm behind Dot™ in collaboration with global health experts from Georgetown University, Duke University and The Ohio State University. Dot is the only family planning app that relies solely on period start dates to determine a user’s individual fertile days.

DiversityNursing.com would like to share this article with you. It features an interview with

DiversityNursing.com would like to share this article with you. It features an interview with

We need a Wednesday feel good story and this is a terrific one!

We need a Wednesday feel good story and this is a terrific one!  “We were just praying that Hudson wouldn’t suffer any effects from the surgery and as far as we can tell he is one perfectly health little boy,” she says.

“We were just praying that Hudson wouldn’t suffer any effects from the surgery and as far as we can tell he is one perfectly health little boy,” she says.

It’s Friday and we thought a feel good story was a good idea. We’d like to share the happy news that a Boston marathon bombing survivor is going to marry the firefighter who took care of her that life-changing and devastating day. He kept coming back to visit her in the hospital. Their friendship and love grew as they got to know each other.

It’s Friday and we thought a feel good story was a good idea. We’d like to share the happy news that a Boston marathon bombing survivor is going to marry the firefighter who took care of her that life-changing and devastating day. He kept coming back to visit her in the hospital. Their friendship and love grew as they got to know each other.

Are you considering furthering your education? Is a PhD a goal of yours? This article will give you good information and some terrific role models. It also encourages you to go for your PhD sooner, rather than later.

Are you considering furthering your education? Is a PhD a goal of yours? This article will give you good information and some terrific role models. It also encourages you to go for your PhD sooner, rather than later. Maybe you’re not looking for a new job, maybe you are, or maybe you want to learn more and gain helpful insight and tips about your field. Perhaps you’re thinking about changing your specialty and if you are, do you need to go back to school? The best way to help you with your decision is with an informational interview.

Maybe you’re not looking for a new job, maybe you are, or maybe you want to learn more and gain helpful insight and tips about your field. Perhaps you’re thinking about changing your specialty and if you are, do you need to go back to school? The best way to help you with your decision is with an informational interview.  Cultural respect is vital to reduce health disparities and improve access to high-quality healthcare that is responsive to patients’ needs, according to the

Cultural respect is vital to reduce health disparities and improve access to high-quality healthcare that is responsive to patients’ needs, according to the

If you’re a parent, you know how daunting those first few months are, not to mention exhausting. Many of you work with new mothers in the maternity ward, doctor’s office, etc. Wouldn’t it be helpful to offer more education about SIDS and how to care for a newborn?

If you’re a parent, you know how daunting those first few months are, not to mention exhausting. Many of you work with new mothers in the maternity ward, doctor’s office, etc. Wouldn’t it be helpful to offer more education about SIDS and how to care for a newborn? All nurses work to improve health outcomes and help monitor and manage disease. But community health nurses work in traditional public health settings and focus on the overall health of an entire community or multiple communities. Community health nursing is also known as public health nursing.

All nurses work to improve health outcomes and help monitor and manage disease. But community health nurses work in traditional public health settings and focus on the overall health of an entire community or multiple communities. Community health nursing is also known as public health nursing. Washington DC area philanthropists Joanne and Bill Conway have committed to a $5 million gift to support our CNL program, funding the education of more than 110 new nurses over five years, beginning in 2018. The Conways, who gave a similar gift to UVA Nursing in 2013 are, with this transformative gift, renewing their pledge to encourage a broader diversity in the students who enroll in this program.

Washington DC area philanthropists Joanne and Bill Conway have committed to a $5 million gift to support our CNL program, funding the education of more than 110 new nurses over five years, beginning in 2018. The Conways, who gave a similar gift to UVA Nursing in 2013 are, with this transformative gift, renewing their pledge to encourage a broader diversity in the students who enroll in this program. All Conway Scholars (entering this summer `17, to graduate in 2019) receive a year-long grant for tuition and related expenses ($24k over the year). The new gift, which will begin funding students in 2018

All Conway Scholars (entering this summer `17, to graduate in 2019) receive a year-long grant for tuition and related expenses ($24k over the year). The new gift, which will begin funding students in 2018